Schostakowitch, Sonata for Cello and Piano Op40

Schostakowitch, Sonata for Cello and Piano Op40

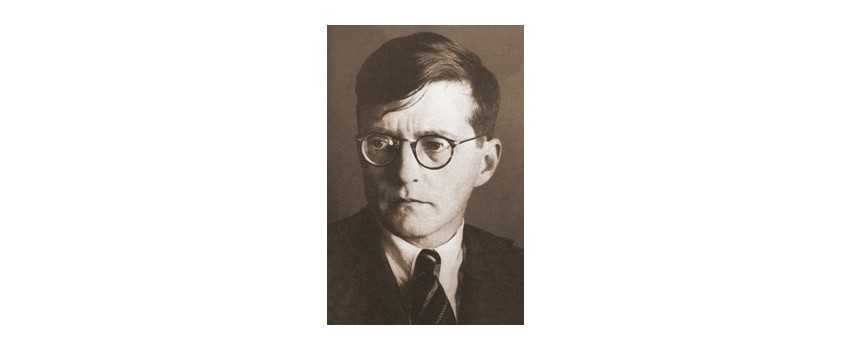

Dmitri Shostakovich was a renowned Soviet composer whose music continues to captivate audiences around the world. His unique style blended elements of innovation, political commentary, and emotional depth, making him one of the most fascinating figures in the history of classical music.

Early Years and Musical Prodigy

Born on September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Shostakovich showed prodigious musical talent from a young age. Although he didn't begin formal piano lessons until he was nine, his progress was rapid, and by the time he was a teenager, he had already composed his Symphony No.1. This symphony, premiered on May 12, 1926, showcased his astonishing originality and marked the beginning of a prolific career.

The Soviet Struggle

Shostakovich's career took flight during a tumultuous period in Soviet history. As the Soviet regime under Stalin tightened its grip on the arts, composers were expected to create music that exalted the glory of Mother Russia and inspired patriotic sentiments. However, Shostakovich's inclination to explore the darker side of human existence often clashed with these expectations, leading to intense scrutiny and controversy.

The Nose and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District

In 1930, Shostakovich faced criticism for his operatic fantasy, "The Nose," which was denounced as "bourgeois decadence." Despite this setback, he found temporary respite with his Piano Concerto No.1, which cleverly incorporated irony that went over the authorities' heads. However, his follow-up opera, "Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District," proved to be his undoing. After Stalin attended a performance and was deeply offended, Pravda, the official Soviet newspaper, published a scathing review, condemning the opera as an "orgy of depravity."

The Symphony No.4 and Survival

Undeterred by the backlash, Shostakovich continued to push artistic boundaries with his Symphony No.4. This symphony, characterized by inconsolable despair, reflected his state of mind during this harrowing period. However, under threat of arrest and fearing for his life, Shostakovich withdrew the symphony just before its premiere. It would take another 25 years for the Symphony No.4 to see the light of day. This traumatic experience marked a turning point in Shostakovich's approach to composition, as he sought to navigate the treacherous waters of Soviet censorship while preserving his artistic integrity.

Triumphs and Compromises

Despite the constant pressure from the Soviet regime, Shostakovich managed to create works that satisfied the authorities' expectations while subtly expressing his own dissent and inner turmoil.

Symphony No.5: Triumph Amid Adversity

In an attempt to regain favor with the State, Shostakovich composed Symphony No.5, a work that conveyed a universal message of triumph achieved through adversity. This symphony, premiered in 1937, was hailed as a masterpiece and effectively restored Shostakovich's reputation. However, beneath the surface, the music contained layers of irony and subversion, a characteristic that Shostakovich would continue to employ throughout his career.

String Quartets: An Intimate Outlet

Parallel to his symphonic works, Shostakovich embarked on a remarkable cycle of 15 string quartets. These compositions, often likened to Beethoven's quartets in terms of scope and emotional range, served as a more intimate outlet for Shostakovich's personal expression. He used the quartet form to explore complex emotions, from bleak despair to moments of gentle lyricism. Notable examples include the deeply autobiographical String Quartet No.8 and the hauntingly beautiful String Quartet No.15.

The Leningrad Symphony and Political Dalliances

In 1941, Shostakovich achieved immense success with his Leningrad Symphony (No.7). The authorities interpreted the symphony, intentionally repetitive and grinding, as a testament to Soviet resilience during the siege of Leningrad. However, beneath the surface, Shostakovich subtly conveyed his own dissatisfaction with the regime. This delicate balance between appeasement and dissent became increasingly challenging as Stalin's regime intensified its scrutiny of artists.

The Dark Years and the Thaw

The post-war years brought further challenges for Shostakovich. In 1946, his neoclassical Symphony No.9 was censured for its alleged failure to reflect the spirit of the Soviet people. Two years later, Shostakovich faced renewed criticism from Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's ally, who denounced composers for their "decadent formalism." Forced to publicly apologize and vow to create more politically aligned works, Shostakovich retreated into more introspective compositions, such as his deeply introspective String Quartet No.4 and Violin Concerto No.1.

The Thaw and Symphony No.10

Stalin's death in 1953 marked a turning point in Shostakovich's life and career. With the easing of restrictions, he felt emboldened to express his true feelings more openly. In 1953, he unveiled his Symphony No.10, a vitriolic indictment of life under Stalin's rule. This symphony, with its searing intensity and emotional depth, revealed the pent-up frustrations and anguish that Shostakovich had endured for years.

Later Years and Legacy

In the final two decades of his life, Shostakovich's music took on a more somber tone. His compositions became increasingly preoccupied with death and existential themes. The loss of his wife, Nina, in 1954 profoundly affected him, and his music reflected his deep sorrow. Works such as the Cello Concerto No.1 and the String Quartet No.8 showcased a distorted version of Shostakovich's personal musical motto, DSCH, representing his struggles and despair.

Despite his personal hardships, Shostakovich continued to compose lighter music, such as the delightful Piano Concerto No.2, which showcased his playful side. However, the overall trajectory of his music became increasingly introspective and contemplative. His final string quartet, with its adagio movements filled with dark despair, mirrored the loss of close friends and the defection of his colleague, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, to the West. Only in his last completed work, the Viola Sonata, do we find a sense of serene acceptance, as if Shostakovich had finally found inner peace after a lifetime of struggle against authority.

Conclusion

Dmitri Shostakovich's life and music are a testament to the power of artistic expression in the face of adversity. His ability to navigate the treacherous waters of Soviet censorship while maintaining his artistic integrity is a testament to his genius. Shostakovich's music continues to resonate with audiences worldwide, reminding us of the complex interplay between art and politics. His compositions, marked by emotional depth, innovation, and political commentary, ensure his enduring legacy as one of the most significant composers of the 20th century.

Schostakowitch, Sonata for Cello and Piano Op40

Shostakovich, Romance From The Gadfly For Cello (SJ Music)

Shostakovich, Sonata Op. 40 for Cello (Peters)

Shostakovich, Sonata Op.40 for Cello (Sikorski)

Shostakovich, Cello Concerto No1 Op107 Cello and Piano (Peters)